Arab Views of Their World

For the first time in Singapore, we can soul-searchingly look at the Middle East and the world at large through the lens of internationally renown artists with roots in the global Arabic community.

The Singapore Art Museum, in conjunction with the Barjeel Art Foundation, is currently showcasing 16 of their reputable and yet thought-provoking art works in its “Terms & Conditions” exhibition.

So we catch glimpses of the recent Arab spring in Egypt in Moataz Nasr’s “Elshaab” and Raafat Ishak’s “Nomination for the Presidency of the New Egypt”.

“Elshaab” comprises 25 painted ceramic figures that represent the varied men and women in Egyptian society that had taken part in bringing about the demonstrations that forced the country’s president, Hosni Mubarak, to step down in February 2011.

The extent of the odds against these fearless “freedom fighters” can been seen when you closely examine these pieces of glazed pottery: all bear injuries. And riot police are depicted as dragging a female protestor along the floor; having ripped her clothing to such an extent that she is seen wearing only her underwear.

With their eventual success, different Egyptian groups and individuals have sprung forth with proposals of alternative models of governance. Skeptical of what had been put forward, Ishak’s installation spells out a manifesto for a new political party to contest in the country’s election. Its Arabic text emphasizes the need for better food distribution and land cultivation by revisiting the highly controversial proposition of re-flooding the Nile River.

Little wonder then that Huda Lufti’s “Democracy is Coming” to Egypt has the country’s iconic singer, songwriter and film actress, Umm Kulthum, looking at the ominous fly-over of fighter jets in a disenchanted fashion.

The ongoing Israeli and Palestinian conflict is also brought to our attention by Kader Attia’s “A History of a Myth: The Small Dome of the Rock”, Jananne Al-Ani’s “Shadow Sites II” and Sharif Waked’s “Chic Point”.

Attia’s installation reflects on the contentious historical terrain of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem: its Jewish community continues to maintain that the temple of Solomon was built there first while its Muslims hold fast that their prophet Mohammed had used this rock to ascend to paradise. At the same time, it expresses the artist’s concern over the views held by Western countries on this matter.

Al-Ani’s video art pans an aerial view of the West Bank and Jordanian country connected to the Israeli Palestinian conflict, accompanied by the hum of the plane from which this artwork is shot. And so succeeds in getting us to expect yet another impending aerial bombing even though the evidence of past catastrophes of similar shelling on this landscape remains invisible to us in the aircraft.

Waked’s video art offers, tongue-in-cheek, to Palestinian men in the West Bank and Gaza the appropriate clothing to wear should they need to go through an Israeli checkpoint. He was inspired to create shirts that expose their lower backs, chests and abdomens as the Israeli state views their bodies as a dangerous weapon and has had to subject them to humiliating strip searches when they needed to cross its checkpoints.

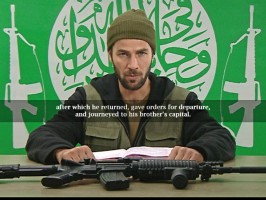

Continuing with this sadly comic approach is Waked’s “To Be Continued…” It takes a swipe at the concept of the Muslim suicide bomber by hiring the poster boy for both Arabic and Israeli cinema to play the part in this video art.

Palestinian actor Mohammad Bakri, in character, recites the never-ending stories in “One Thousand and One Nights” at his last testimony. The suicide bomber’s aim, in this case, is to delay the time he would be sent on the mission of blowing himself up.

We are also asked to reflect on the Lebanese civil war that lasted from 1975 to 1990 by Raed Yassin’s “7 Porcelain Vases”, which recreates his country’s ancient tradition of recording victories at battle on vases for the sake of posterity. In this case, he wanted noted down the 7 key battles of this civil war.

But the circular curvature of these ceramics belies the fact that closure is near impossible as the number of memories of this war are as varied as the million who had left the country then (and not counting the 120,000 who died).

Yet another memory of war-torn Lebanon is Akram Zaatari’s untitled work which showcases “Nabih Awada’s Book of Letters from Family & Friends”. These detail intimately, politically and yet sensitively Awada’s detention in an Israeli prison from 1988, at age 16, for 10 years for being a communist resistance fighter. Thus offering additional insights into this fight – ones official records do not dwell on.

Then there is Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s “A Carpet”, which has a space rocket woven prominently in its centre. Thus attempting to trace the covert ideals of space exploration in the Middle East, and what these rockets stand for after the Six Day War between Israel and Arab States in 1967.

Raising the question of a war in the scale of global proportions is Mona Hatoum’s “Plotting Table” – a battle table with its top carrying a map of the world made out of green lights. It bears similarities to that which Napoleon had used to organize his army before attacking – for the sole aim of conquest. Inevitably, we are forced to ask in horror ‘who is planning to attack?’ ‘Who wants to rule the world?’ ‘How many are going to die?’

This shift onto a global focus is continued in Adel Abdessemed’s “Fatalite”. His installation comprises a forest of 7 microphones made from hand-blown Murano glass and that are mounted on extremely high tripods. Thus, placing them beyond our reach and so denying us the priceless opportunity to speak more loudly. And in turn, denying us the necessity of being listened to.

Next we are confronted by Adel Abidin’s “Three Love Songs” – a tri-channel video art featuring young, blonde and seductive singers in stylized music videos. Despite sounding and looking like they are crooning love songs in ancient Arabic, they are all singing specific Iraqi songs commissioned by Saddam Hussein for glorifying his rule and regime!

We cannot but be persuaded to re-look at the images we are constantly exposed to and ask if they are used to manipulate our consciousness in any way.

Just as the constant emails we receive from Nigeria or Russia attempt to play with our sympathy – in order to con us into parting with our money as part of an advance-fee fraud. And Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joriege’s “A Letter Can Always Reach its Destination” magnifies their aim by creating holograms of actors hired to emotionally read out loud these cyber-scamming letters.

These global perspectives are persuasively plausible as Hatoum now lives and works in London and Berlin. Abdessemed has made New York his permanent home and Abidin dwells in Helsinki. Even then their present alternative life has its fair share of social issues.

And one such is explored by born-in-France and London-based Zined Sedira’s “Mother Tongue”. This video triptych shows her Algerian mother speaking to her in Arabic while she replies in French. And when she asks her daughter in French, the little girl answers in English! Not surprisingly, when grandmother and grand daughter try to communicate with each other, they are reduced to bodily gestures and awkward smiling silences.

Grab our rare opportunity to look at the world through Arab lenses at the Singapore Art Museum at 71 Bras Basah Road, Singapore 189555. This first-ever exhibition here ends on 8 September this year.

Singart

Singart