The Ever Evolving Ukiyo-e

Having given, in a nutshell, what STPI’s coming summer show “Edo Pop: The Graphic Impact of Japanese Prints” entails in my SingArt post, “Japan In Creative Focus”, lets move onto the historical development of ukiyo-e to better appreciate what this exhibition will display.

So what are ukiyo-e prints? And how has it progressed to the exemplary contemporary art we will see at STPI?

Ukiyo-e is an established field of woodblock prints and paintings that arose and gained prominence in Japan between the 1600s and 1800s, a time frame known as the Edo period in Japanese history. Edo, or modern day Tokyo, was the seat of government for the military dictatorship; under which the city’s economy grew at bullet train speed.

The boom’s main beneficiaries were a class at the bottom of Japan’s social order – the merchants (or chonin). With bulging purse strings, they were able to indulge in entertainments, like kabuki theatre, courtesans and geishas populating the Yoshiwara ‘pleasure districts’.

Hence ukiyo-e first started primarily on subject matter revolving round beautiful women, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers and erotica. The term ‘ukiyo-e’ itself means ‘pictures of the floating or buoyant world’, definitely an apt description of the euphorically hedonistic lifestyles it depicted.

This singular focus on what to paint or print was further cemented by its popularity with the chonin, who had become wealthy enough to lavish what they had earned on these works of Japanese art, with which they decorated their homes.

Expectantly, ukiyo-e evolved to further serve its aesthetic function: the early popularity of Hishikawa Moronobu’s paintings and monochromatic prints of beautiful women inevitably gave way to colour ones, which began as commissioned works pricy enough for a myriad of hues to be added by hand.

As the mid 18th century approached, artists such as Okumura Masanobu started using multiple woodblocks to print separate areas of an ukiyo-e with differing colours. Come the 1760s, Suzuki Harunobu pioneered the production of full colour ukiyo-e prints (nishiki-e or ‘brocade pictures’), which spelt the end of existing techniques that produced only 2- and 3-coloured versions.

With nishiki-e becoming the only acceptable standard, the use of 10 to as many as 20 woodblocks transformed ukiyo-e to the multi-hues they are still renowned for to this day.

Even then the defining feature of most early ukiyo-e monochromatic prints remained – that of the distinctive flat line. In those initial forms, it was the only printed element.

With the advent of colour, this typical line continued to dominate as ukiyo-e’s composition remained noted for the arrangement of forms in flat spaces: the human figures were characteristically arranged devoid of depth – the well-prized focus was on vertical and horizontal relationships, as well as minute details such as flowing lines, perfect shapes, and classic patterns that, for example, decorate elaborate clothing adorning the geishas or kabuki actors.

In nishiki-e, the contours of most coloured areas are still sharply delineated by these fluidly distinct lines. In this way, the aesthetics of flat areas of colour definitively differed from the modulated ones expected in Western artistic traditions, and from other prominent then-current practices in Japanese art patronized by the upper classes; namely the subtle monochrome ink brushstrokes of the Zen Buddhist zenga brush painting or the tonal colours of the Chinese-influenced Kano schools’.

Given the number of colours that were needed to produce 1 edition of nishiki-e, artists rarely carved their own woodblocks. They would only apply their artistry in their design while a carver would undertake the labourous task of cutting the blocks of wood and a printer meticulously inked and pressed the woodblocks onto handmade paper. This symbiotic collaboration was totally financed by a publisher; who, in turn, promoted and distributed the prints as well.

Moreover, as all printing was completed only by hand, the print makers were able to achieve effects unattainable with the printing machines existing back then, such as the blending or gradation of colours on the printing block.

Yet public credit was given only to the artist and the publisher in this collaborative endeavour: their seals alone marked a published piece of ukiyo-e print.

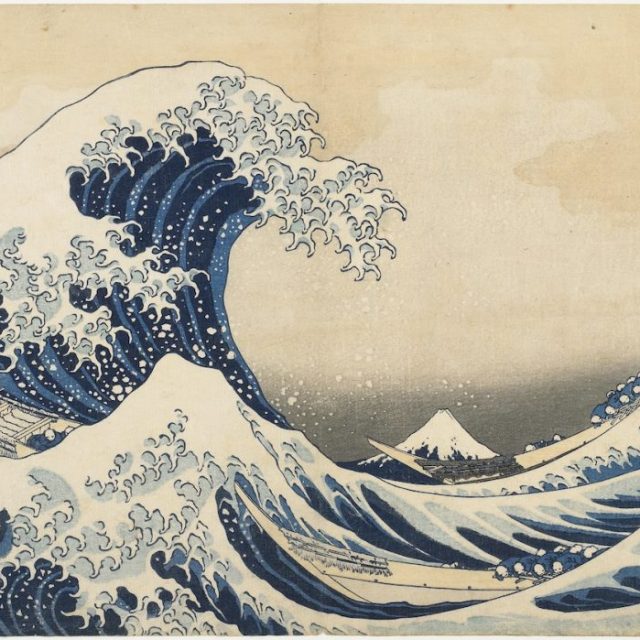

Having reached the pinnacle of technical development, the evolution of this art form shifted to changing its subject of focus: while grand masters like Torii Kiyonaga, Kitagawa Utamaro and Toshisai Sharaku created countless portraits of beauties and actors right to the late 1700s, this was supplanted by artistic depictions of Japanese landscapes in the 1800s; of which Katsushika Hokusai’s “Under The Wave Off Kanagawa” and Utagawa Hiroshige’s “53 Stations of the Tokaido Road” series are works still best known internationally today.

This shift to representations of landscapes, as well as travel scenes and pictures of nature, especially of birds and flowers, along with stories from history and folklore, was a direct response to the introduction of the Tenpo Reforms in Japan from 1841 to 1843.

The array of economic policies, which the Tokugawa Shogunate presented and implemented, resolved problems in military, agricultural, financial and religious systems in its country; as well as placed restrictions on entertainment – the reformation sought to suppress outward displays of luxury too, including the depictions of courtesans and erotica in ukiyo-e.

From then onwards, ukiyo-e prints must bear the censor’s seal of approval as well!

The landscape prints that, hence, evolved mirrored the way Chinese ink brush painters composed their paintings: the ukiyo-e masters similarly relied heavily on imagination, composition and atmosphere; rather than the strict observance of nature favoured by the Western artistic practices of the time. An ukiyo-e artist need not sit before the scenic spot that had ignited his fancy to creatively design its print.

Following Hokusai and Hiroshige’s deaths was the Meiji Restoration of 1868 – a chain of events that restored practical imperial rule of Japan under Emperor Meiji. The resulting technological and social modernization of the country catalyzed Japan’s emergence as a contemporary nation in the early 20th century. Unfortunately, it spelt the significant decline in ukiyo-e production, both in quantity and quality.

With rapid Westernization of the Meiji period and fierce competition from photography, woodblock printing resorted to serving journalism. Consequently, ukiyo-e as an art form was extremely endangered, and became seen by modernized Japanese as a remnant of an obsolete era – they resolutely turned their discerning tastes away from it. By the 1890s, this more than 200 year-old tradition was well and truly dying in Japan.

Yet, when ukiyo-e was at its peak, it was 1 of the West’s central perception of Japanese art. As of the 1870s, it and its culture and aesthetics had tremendous impact on art in Europe: Japonaiserie was inspirational to impressionists, like Degas, Manet and Monet, and post-impressionists, including van Gogh, as well as cubists and art nouveau artists – Toulose-Lautrec being a prime example. Its influence is even remarkably obvious in more modern works; as illustrated by Roy Lichtenstein’s “Drowning Girl” and David Hockney’s “The Weather” series.

From the early 20th century, avid Western interest in prints of traditional Japanese scenes fortuitously revived print-making in the land of the rising sun: shin-hanga refers to new wood block prints that maintained the time-honoured ukiyo-e collaborative system needed in their creation, printing and distribution; while sosaku-hanga promotes the drawing, carving and inking of a printed artwork by 1 artist; with the over-arching aim of guaranteeing self-expression.

The latter soon surpassed the former in terms of sustained innovative interest and today, sosaku-hanga artists like Korishiro Onchi, Unichi Hiratsuka, Sadao Watanabe and Maki Haku are well known the world over.

Since the late 20th century, many Japanese artists, as well as artistic foreigners, like Emily Allchurch, make works of art on contemporary or still relevant subject matter inspirationally in the Edo ukiyo-e fashion, with antiqued techniques married to those imported from the West, be it perspective or screen-printing, etching, mezzotint and mixed media.

Truly, this unique style, once endemic to just Japan, is here to stay.

Feast on the sumptuous selection of Edo period ukiyo-e, along with an array of ukiyo-e inspired contemporary art, which STPI will showcase from 12 July to 13 September this year.

The Singapore Tyler Print Institute is at 41 Robertson Quay, Singapore 238236.

Singart

Singart