Starring: Paper, paper & PAPER!

Trust STPI to turn an exhibition on its head: it has taken the focus away from the artists and their residencies by making paper the star of its current group show.

Its “Looks Good On Paper” embarks on the least tread ambition of sailing us along the creative journey of diverse routes paper – handmade or otherwise – can technically and ingeniously take in fleshing out what has been artistically conjured.

The resulting range of displayed artworks is an impressive exemplification of not only the artists’ limitless imaginations and STPI’s extensive innovative technical expertise, but first and foremost of paper’s equally invigorating versatility and malleability as an inventive medium.

So the exhibition starts by rolling out its stars of the show with their more conventional artistic uses, like Teppei Kaneuji’s “The Eternal (Singapore)” series of screen printed paper which he subsequently cut into strips that are then aesthetically draped fluidly cascading over plastic hangers and stands, and Ryan Gander’s “The redistribution of everything that is good” of notebook paper his young daughter had ardently reshaped by razor-sharp scissors and he then systematically ‘tessellated’ onto black inked aluminum plates.

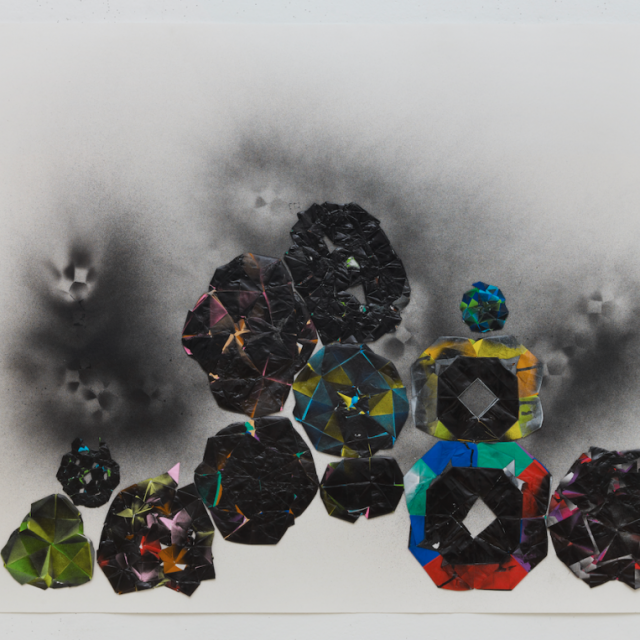

Hague Yang’s fascination with origami takes folding coloured paper to another playful plane: her “Non-Folding – Geometric Tipping #43” morphed from using origami-ed 3-dimensional shapes as stencils against which paint is sprayed on white paper. These paint-stained origami stencils she next appealingly collaged into her “Non-Folding – Scenarios of Non-Geometric Folding #4”!

While we are all familiar with the shape-holding foldable nature of dry paper, Richard Deacon’s “Beware Of The Dog #1” clearly illustrates that a wet handmade sheet of paper pulp can keep the shape it is crumbled into – as long as it is thus treated at an 80% semi dry state before the remaining 20% of water is subsequently removed.

Wet paper pulp’s malleability is further demonstrated by Ronald Ventura’s “Shadow of the Forest” series: he embossed handmade paper by drying their dripping wet sheets unconventionally draped over his collection of recycled pieces of carved furniture wood before figuratively montaging them and paper rubbings of the said same crafted timber into primeval fauna.

In reverse, Wu Shanzhuan & Inga Svala Thorsdottir’s “4 x 5 Perimeter of Little Fat Flesh – Yellow” showcases the indented emboss effect when 1 acrylic flat shape is concurrently and repeatedly tessellated mosaic-floor-tiling-like over an entire sheet of yellow wet paper pulp; while Ryan Gander’s “Seriously Retinal/Seriously Poke (morton arboretum)” highlights the same effect with French curves unusually used as plates to print elated configurations in a riot of colours a la Henri Matisse’s cut outs.

And the embossed indents are not confined to being made by flat surfaces or plates, as attested by Hague Yang’s “Colour-blown Craters and Dunes” series. Here, a chaotic array of rice grains, Jew’s ears, along with as an expansive selection of fresh herbs and veggies were partially pressed onto wet paper pulp, and only gingerly removed before the fibrous panes completely dried.

By pushing an insoluble and waterproof object all the way through the entire thickness of wet paper pulp enabled Ashley Bickerton to produce a holey Swiss cheese effect on the subsequently desiccated Martian-like landscapes in his “Graffiti Mountain” series.

Han Sai Por’s dynamically volatile “Fly Through the Wind” succession of artworks and Do Ho Suh’s subtly comforting “Father & Daughter” demonstrates what happens when objects laid on highly damp paper pulp are not removed as the latter thoroughly dries out – their threads, ever so fine and delicate, become automatically bonded with the fibrous paper pulp.

This natural binding ability of paper pulp’s water soaked fibers is the primary driver for Hague Yang’s successful execution of her remarkable “Spice Sheets” series – in this instance, every 50 g of wet pulp could hold onto up to 30 g of dried ground spice of every conceivable edible plant species; making her groundbreaking art into, quite literally, a hard science.

It is this same innate characteristic that allowed Han Sai Por to hand sculpt purely wet pulp into densely and stiffly solid 3-dimensional crusty thoroughly dried forms in her artistic run of “Tropical Fruit” as well; and Handiwirman Saputra to trendily ‘sketch’, with dainty tweezers, on dry translucent abaca paper with delightfully wet opaque cotton pulp squiggles in his genteel ‘embroidered’-like “Suspended Forms #04”.

But we can do more than just paper pulp draw – there is, of course, paper pulp painting too. In “Little and Without Tears”, Suzanne Victor lovingly poured ultra diaphanous layers of watery pulp onto crystal clear acrylic sheets with a trusty ladle. Upon drying, the added binder within the semi-transparent film of paper fibers magically adhered the super fine fiber coatings to the acrylic.

Shambhavi took this sublime technique in the exact opposite direction by creating a totally contrasting artwork – drawing inspiration from how industrious farmers still plant with their strong hands, she as rigorously rubbed and shearing-ly smeared thick wet pulp with the delicate palms of hers onto richly pigment stained handmade paper; birthing an emphatic collection of “Hathiya/Elephant Cloud”.

The tradition tested understanding that paper can range from compact opaque to slender translucence, in turn, inspired Shirazeh Houshiary in her artistic rendition of the series “The River Is Within Us”: she gamely synergized the transmission of knowledge from the ancient age of chiseled writings on stone tablets to modern man’s current use of iPads by back lighting her dimensionally impressive works of sheer handmade, hand-dyed and hand-printed linen-papered wall art.

And the key concept that varying a paper’s slimness during its making can generate discernable changeable degrees of its light transmission has yielded yet another time honoured paper mill innovation – the elegant ethereal limpidity of water marking. By creating wispy thin swirling-like watermarks in a collection of otherwise milky opaque paper screens, Ryan Gander crystallized his original and yet exact interpretation of exotic Japanese calligraphy with his “Toki no nagare, or There are people having more fun with prostitutes”.

Therefore, the crux of handmade paper’s versatility lies in working it while it remains wet. In this flexible state, Suzanne Victor was able to captivatingly and sensuously perform her “Holding 2”, where she laid on top of huge slips of wet differently hued paper pulp while enthusiastically ripping them into strips of every length and width; gleefully peeling back the abundant layers.

Yet paper’s tough stiffness in its completely dried out condition may still need enhancement, like adding konnyaku – a Japanese root-based gelatin. This stays true even for handmade cotton – other wise known as abaca. But once added, crumbling the rigid leathery-like product makes it amazingly pliable enough for stitching together a durable wearable more-than-life-size out-of-this-world head mask in the likes of Eko Nugroho’s “I Am An Animal of My Own Destiny”.

Why does paper have a malleability and versatility even more substantial than Leonardo Wilhelm DiCaprio’s acting and film producing repertoire? Well, it lies with its fibrous nature, and that divergent linter materials fluctuate in individual yarn lengths.

Casting the right paper, thus, becomes as complex as assembling brilliant leading actors and actresses worthy of an equally exceptional script and director with a correspondingly big Hollywood budget and crew. Only then can STPI’s artists-in-residence continue to create out-of-the-box stellar works worthy of winning more than the international art world’s equivalent of the globally acclaimed Oscar nominations.

Catch this sneak peek into the thrillingly exquisite paper-starred creations resulting from STPI’s technical casting couch before its run on “Looks Good On Paper” at 41 Robertson Quay, Singapore 238236 ends on 23 December.

Singart

Singart