Well Beyond Black & White

The winsome imaginative promise of my mental amalgamation of Indonesian Christine Ay Tjoe’s Second Studio (2013) with Singaporean Jane Lee’s painting process has at last witnessed tangible harmonious representations through Zhu Jinshi’s 20 odd coloured paintings showcased in his “Presence of Whiteness” exhibition.

The Beijing-based pioneer Chinese abstract artist’s 2012 to 2016 works delightfully bear Tjoe’s trademark delicacy of inner personal thoughts, melancholy, struggle, pain and happiness in the context of the motherland’s progressive changes in socio-political experiences; barring only the fragile femininity imbueing her art.

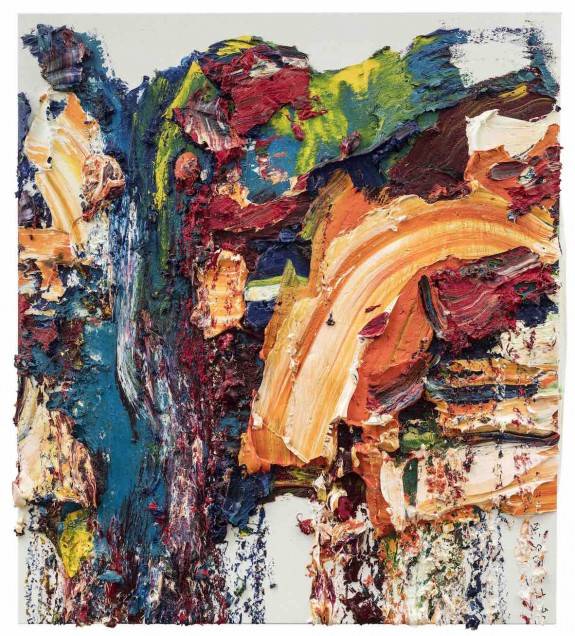

Instead Zhu maintains his signatory boldly masculine renditions; achieved through his vigorously ardious pulling, pushing, flipping and shovelling of custom-made palette knives over the canvas; composing revolutionary moments of action while mindfully debating where to fill, where to empty, where to collapse, where to fall, where to determine, and where to hesitate in his ingenious construction of the artworks’ presence of whiteness – reminiscing Lee’s painstaking artistic philosophical pounderings of deconcontructing and reconstructing the fundamental constituents of a painting that has propelled her to slavishly mix paints to the precise hues, shades and consistencies to encapsulate their successful applications onto the lack of canvas thereof.

However, the impetus of Zhu’s philosophy differs starkly from Lee’s: his pursuit is driven primarily by a mindblowing dialectic of vibrant colour as an ambitious concept. More precisely, his works expound that the return of white to an object through the medium of paint renders white all the more to being an object, rather than that of a painting.

A whiteness that signifies not only a minimalist reduction to the extreme of a totally blank canvas, but also carries with its emptiness the potency of the inner mind; rendering the collision and conflict of these two roles an intersection of cultural language and syntax, as well as a vivid embodiment of every decision Zhu makes when confronting a blank canvas, colour AND paint.

Instinctively, his colours resultantly become confidently conveyed three-dimensionally through his thick applications of paint; wholeheartedly embracing the hues’ splendidness through their evolving materiality while directly facing the medium’s surprising challenges. In these instances, the artist’s agent naturally becomes embodied in time, while the presence of whiteness is where the moment freezes.

Hence, in keeping with his “Detached From Colour” series of paintings, the brilliantly hued shades become consequently transformed into enriched bodily forms traversing between a canvas’s whiteness and their riot of colour-filled three-dimensional space. And as the different levels of white paint grow fearlessly, colour and paint may expand, overlap or hide in crevices, edges or cracks of whiteness – resonating with the traditional idea of liu bai; of leaving a message of idle moments through the empty spaces in a work of art.

Paint invariably becomes a game played out by a materialised body and an escalating vision; where the simplicity and thickness of painting becomes the crucial point of paint and space’s performance, and every centimetre of the medium’s accreditation signifies absence’s indispensability.

With this negation of aesthetic’s ecstasy through this vehicle, Zhu’s paintings are therefore not to be viewed in stillness: in Western Hills and Such a Master, the quinessential subject is not immersed in the work. It is instead made to stand out; marching forward on an elusive ever ascending and descending path filled with mindboggling obstacles and doubts – the rumbling rivers of paint soar on top of the waves, rush to the forest’s summit, fall into the mountain’s valleys, and hang midway off a cliff; astonishing Mother Earth.

Yet the crescendo comes when time breaks to halt the paint, ending space with an absence of this humble artist’s medium – an emptiness that is also the mean’s revelation. Without a doubt then, the core concepts encapsulating calligraphy invariably winds through Zhu’s canvases – just as his never ending argument with eastern tradition continues to vanish with his use of paint; revealling the compelling extent the philosophical roots that birthed his 1985 Sunshine has remained in his ever evolving artistic practice – he is still to this day alienating himself from the modernism of western abstract art with a touch of Chinese calligraphy aestheticised into abstraction.

Ruminate on Zhu Jinshi’s success in creating an aesthetic that beautifully uses the east as an answer to the questions posed by the west while sharing Christine Ay Tjoe and Jane Lee’s contemporary artistic sensibilities before his “Presence of Whiteness” exhibition ends at Pearl Lam Galleries, 15 Dempsey Road #01-08, Dempsey Hill, Singapore 249675 on 5 March.

Photo credit: Pearl Lam Galleries

Singart

Singart