Finding Eden

The western world, through its former national allegiance to Christianity, has historically been obsessed with finding God’s original Garden of Eden. Those who believed that it is located geographically on Earth cited as evidence Genesis 2:8 in the Holy Bible: ‘And the Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east…’

Since the Middle Ages, Asia has been seen as the utmost extreme eastern region in our world. So its European mapmakers had repeatedly placed His Paradise in our backyard.

It comes as no surprise then that Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1614 “Map of West Asia and Map of East Asia” located Eden here, ‘where the soil was fertile… and Adam, Eve and the tree of paradise in the Middle East… (with) the Ark wedged in a mountainous region of East Asia’.

During Asia’s chapter of colonized history, the west’s mindset of studying our tropical Eden stems from many purposes, of which 1 was to remake it into the colonizer’s image. This salient aim is strongly echoed in Singaporean Donna Ong’s 2 works of art: “Letters From The Forest (II)” and “The Forest Speaks Back (I)”.

John Walker’s 1817 “A Map of Java” is even more telling: it charts major cultural and historic monuments and locations of mineral deposits across Java; along with a road that implied colonial intentions to survey and master their new colony and its bounty.

That Indonesians today hold strongly to the fact that the rape of the Mooi Indies began from colonial times, with the spice trade, and continued today by administrations, corporations and conglomerates is evident in “Pandora’s Box”: Maryanto’s artwork depicts his homeland as once beautiful resource-rich landscapes that have been ravaged by industry. All that remains is charred, blackened earth.

India’s Jitish Kallat’s “Annexation” drives home this sentiment: the price Asia has paid for the continual plunder that has built its modern commercialization is too high – daily living for the masses of poor in his homeland remains a grind for survival.

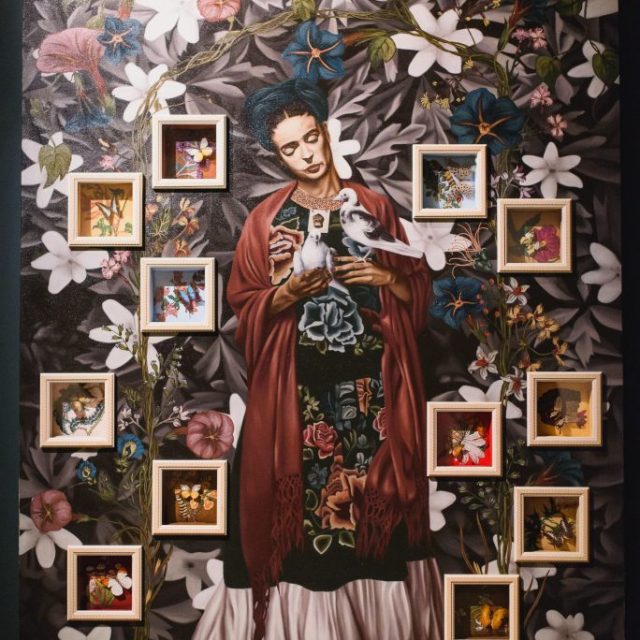

How could this be so, given the independence Asian nations have gained from their former European masters? Filipino Geraldine Javier’s oil on canvas, “For She Loved Fiercely, And She Is Well-Loved”, shows us why: we all descend from the fallen Eve in the Bible’s Garden of Eden.

This rootedness in sin leads to other adverse consequences as well: Indonesians, Agus Suwage & Davy Linggar’s “Pinkswing Park” depicts our contemporary Garden Paradise with its modern ‘Adam ‘ and ‘Eve’ highly conscious of their state of undress. The sad result is deliberately artificial beauty after filtration through an ideal lens that heightens anxiety over the human body.

Public outcry that this art work has crossed acceptable boundaries has led to its withdrawal from its group exhibition and the show itself banned in Indonesia; shattering illusions about freedom of creative expression – its utopia, derived since national independence, was altogether too short-lived.

Loosing our garden city Shangri-La is implied too, given the Singapore government’s ambition to raise population numbers to 6 million. Our Ian Woo’s “We Have Crossed The Lake” depicts a metropolitan home that faces landscaped greenery increasingly illusively out of reach – rampantly growing tangle of vines are slowly but surely obscuring him from its bucolic view.

Shannon Lee Castleman, from America, shares this sentiment after having lived on our island for some time. Her “Jurong West Street 81” shows what we already know: most Singaporeans, living in high density high rise Housing Board Flats, face the unsavory daily prospect of looking into their neighbours’ homes whenever they gaze out of their windows.

That this divorces us even more from the benefits of being 1 with Mother Nature is spelt out by Malaysian Chris Chong Chan Fui’s depiction of Kuala Lumpur’s grid-like homogenuous high-rise buildings in his “Block B”.

Unfortunately, the malice of modern living does not end there. Mainland Chinese China’s Gao Lei’s “Cabinet” raises yet another red flag: the rapid urbanization and globalization of China have unmoored its younger generation from traditional anchors of identity, casting them adrift as sole survivors of a post-apocalyptic universe.

And Indonesia’s Made Wiantia’s “Air Pollution” lifts a 3rd: urban development from booming tourism is crowding Bali into a built-up jungle of industrial materials that is racking environmental havoc.

The outcome is symbolized by Singaporean Tang Da Wu divorcing his “Sembawang Phoenix” from his “Sembawang”: the days his and other artists villages can remain in a kampong environment are irrevocably coming to a definite end.

Then we have Indonesian Yudi Sulistyo’s “Realizing Dreams”. Despite its uplifting title, it dashes our hopes of Eden even further – its grounded war machine wrecks reveal Asia’s reliance on technology to achieve national ambition and power as unfortunately hollow and illusory.

Countries in the Far East that have aspired for Paradise by embracing communist doctrines have not been spared from artist critique either. Mainland Chinese Shen Shaomin’s “Summit” trumpets the promise of ultimate failure for their political ideology. And those who choose to keep resuscitating it have to white wash it the way Vietnam’s The Propeller Group has done with their “Television Commercial for Communism”.

Yet, for the rest of us who have pursued Eden with 1 form of democracy or other, Malaysian Anurendra Jegadeva’s “Love, Loss and Pre-Nuptials in the Time of the Big Debate” has this cautionary tale to tell too: the multi-culturalism embedded within our individual national shores inwardly binds each ethnic group to such an extent, it continues to divide us politically.

Even then, nothing is worse than being willingly blind to these terrors while reveling in humanity’s desperate absurdities: To those who do, Kawayan De Guia’s “Bomba” is a warning: they are on a death-defying disco that will definitely end his Philippines and planet Earth.

Faced with such doom and gloom, Thai Kamin Lertchaiprasert’s “Sitting” suggests that we stop seeking a physical Garden of Eden. Instead, we should attempt to find Paradise by turning our mind’s eye inwards through celestial meditation.

And if we are filled with angst over losing our heavenly Eden in Asia, Cambodia’s Svay Sareth offers this ethereal solution: seek catharsis by embarking on a challenging journey similar to that taken by devout Catholics – a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northern Spain.

Many have completed this Way of St. James since the Middle Ages. As many have, thus, been profoundly changed.

Muse over these thought-provoking art at the “After Utopia” exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum, 71 Bras Basah Road, Singapore 189555. They are on display till 18 October this year.

Singart

Singart