A Confine Of Layered Views

Closed as a jail in 1991, the Freemantle Prison, in Western Australia, has been gazetted for conservation as a historic building. From 1992, tours round its facilities began. And I went on 1 in 1998.

It was my 1st visit to a penitentiary, albeit a defunct 1, and I found the communal spaces clinically spartan. The individual prison cells were even more depressing: each was a very small confine, with an even tinier barred window. Images of inmates grasping the cold bars and peering longingly between them outwards towards freedom clingingly haunted my mind.

I could clearly see why if 1 were to die in such an enforced confinement, his restless spirit would be lingering within, trapped in its sense of incarceration, wailing through the darkest hours of the night. That is till I was shown the highlight of the prison tour.

On the walls of some of these lockups were drawings the prisoners had themselves painted. Done in either the brightest or the most soothing of hues, these realistic representations of Australian landscapes brought the sense of infinite space and equally immeasurable beauty into their otherwise sterile cells in ways that bountifully expanded the horizons set by their heavily bricked partitions.

These paintings must have changed life in jail beyond just being bearable; especially when they had been deemed by the prison warden as aesthetically artistic enough for him to have actively encouraged these creative convicts to go on to work the same magic on the bare courtyard walls that separated them from the rest of the community living in Freemantle.

The results are scenic stretches of Aussie terrain that surpassed the enormity of Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies” exhibited within the Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris, France.

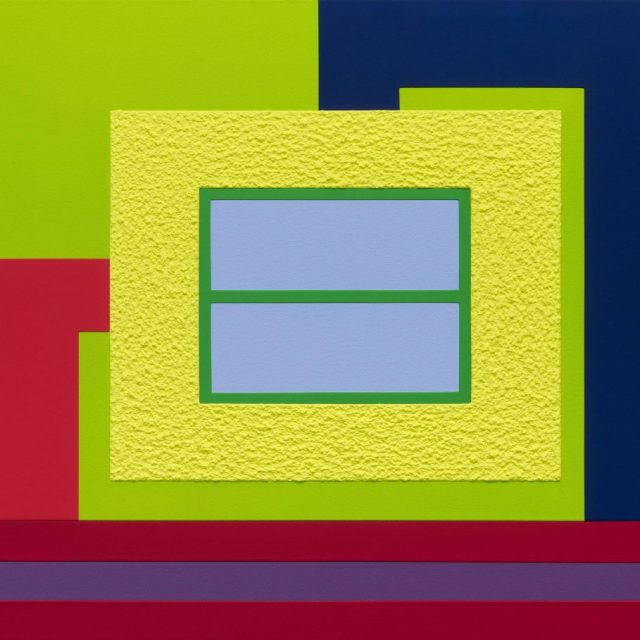

American Peter Halley’s artworks bring these memories and sensations distinctly to mind. As paintings that participate in the renewal of pure abstraction towards an artistic movement that integrates symbolism, figuration and functionality, Halley’s densely coloured and textured works of art obsessively play with rectangular shapes that he reinterprets as structures of prison cells.

For this artist, geometry today offers ‘ a changing multiplicity of meanings, images of imprisonment and dissuasion’. His series of painted cells represent the mental isolation and oppression of jails, hospitals and cities that he sees as global impersonal machines.

His acute awareness of these agents of psychological captivity stems from having moved his artistic practice back to New York in 1980 and the subsequent ironic initial isolated hardships he had faced upon living alone in a bustling metropolis.

Yet Halley sees this initial solitary isolation as crucially important for the momentous development of his craft. Hence he renders his geometric shapes in intensely bright, almost fluorescent, colour palette in ways admirers of his art interpret as a clear movement away from the natural world.

This colourful representation of symmetrical geometries proved to be the very vehicle that allowed his art to reach new peaks, furthering his milieu of work in the creation of his most influential pieces of art, which have gained a showing in internationally renowned museums in the United States as well as Europe. Commercial galleries in London, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Seoul and Tokyo jumped at the chance of representing him too.

Even then, his choice of paints has a 2nd function too: it is Halley’s means of rendering American pop mass culture as a fantasy that leads art to commercially appealing decorative forms. With his use of Roll-a-Tex and Day-Glo paint, Halley thus transcends modern principles as yet another reflection of contemporary society.

At the same time, his pick of geometrical forms serves an added purpose as well: abstraction becomes the mirror of society as in post industrialization, ‘each human being is no longer just a number, but is a collection of numbers, each of which ties him or her to a different matrix of information. There is the telephone number, the social security number, and the credit card number’.

Given his view that man has thus been digitized, Halley also sees his rectangular shapes, linked with a quantity of tubes, as computer chips that invite us to penetrate a reality coded with colours; and see them constructively anchored into yet another contemporaneous issue. Thus engaging us in a dialogue heavily punctuated with a vocabulary related to technology, communication and information fluxes.

And will there ever come a day where those after serving prison sentences become chipped like we do our dogs and cats for the sole purpose of tracking them as a deterrent to falling back into a life of crime? And will its success lead to chipping everyone as dissuasion from embarking upon sinister mischief and mayhem in the 1st place?

If so, will Halley’s geometric shapes remain luminously radiant?

Ponder deeply upon the layers within layers of abstraction at Peter Halley’s solo exhibition at Art Plural Gallery, 38 Armenian Street, Singapore 179942 before it ends on 3 October this year.

Singart

Singart