Beyond Strings Around Mulberry Paper

Chun Kwang Young is fond of saying, “I think the thing I saw first (as a child) was my mother’s face, and then there was mulberry paper. This paper is not just for writing and drawing, but is like the spirit and soul of Koreans.”

But the significant application of both in his pieces of art did not materialize till life changing events shifted his artistic expression away from his highly successful years as an abstract expressionist in the United States.

Rural Korea-born and -bred, Chun could not shake away the feelings of being a foreigner in America. He persistently felt confused, anxious and sad. He was also deeply affected by the social and political events of the 1970s: he personally struggled with the issues of race and class, the moral dilemma of the Vietnam War and America’s excessive consumerism, materialism and scientism. These immensely conflicted with his traditional Asian humanistic views and ideas.

Chun loves nature and back then he wanted more than anything else to live his life in harmony with nature. He attributed this to the fact that as Koreans, their “ancestors lived modestly and simply, and thought all lives should be respected”. Little wonder, he hoped his master pieces “could take this traditional Korean message forward to modern society”.

Though he found some reprieve by successfully expressing his inner turmoil through his early art, Chun grew increasingly impatient with the restrictive western confines of abstract expressionism. Earnestly longing to craft his signature artistic lingo as a Korean artist with resounding victory over his inner struggles, he decided to return to his motherland.

The defining moment that raised Chun to the stature as an internationally renown artist he is to this day came one late Korean spring in 1995: Confined at home by a bad cold, Chun stared at the paper packet of medicine that his wife had tenderly handed to him. Turning the package over and over in his hands, a childhood memory, long forgotten, grew gradually to prominent clarity before his mind’s eyes.

He could see himself as a sickly child once more and his mother was once again dragging the reluctant young Chun to the Chinese doctor in his grandfather’s herbal-scented Chinese medicine hall in their neighbourhood. He was sheepishly dragging his feet as he had “never liked the place (for its) strong odour and the threatening sight of acupuncture needles”. So to alleviate his feelings of dread while the Chinese doctor took his pulse, he was resolutely scrutinizing the multitude of mulberry paper packages hanging from the ceiling above – each containing different medicinal herbs.

With this childhood memory came a second recollection: Korean mulberry paper, known as hanji, is deeply embedded within the Korean heritage as it was once the definitive material used by Korean women folk to trustily wrap medicine, food and herbs, and daintily cover their walls, floors and windows.

This further led to another re-realization: the very act of wrapping harked back to the nomadic life all Koreans once led – these nomads had to pack the few worldly possessions they owned before moving to yet another location to pitch their tents. So every Korean family had an abundance of mulberry paper – it was quintessentially tied to Korea’s history.

With this flood of profound thoughts, Chun elatedly realized that he had finally found a wondrously unique medium to infuse his art with a classic Korean sentiment – he would set upon the western aesthetics of abstract expressionism with the traditional hanji to personify his own personal history.

So for the past 20 years, Chun searched Korea for old books printed on mulberry paper as the resource material for his assemblages. Some are close to a hundred years old and their genres varied from literature and philosophy to politics and religion. He would extract the hanji from novels, diaries, codes of law, the Analects of Confucius, the Book of Mencius, to name a few.

And each piece of these mulberry paper bears the finger prints of countless people who have flipped the scholarly books’ pages – and they “maybe a lady, maybe a man, maybe poor, maybe rich, maybe a teacher and a student…”, as well as the book publishers and printers, the authors, the distributors and the retailers.

By so doing, Chun believes he is not only giving the past a new voice, he is also creating a sense of personal stories and in the totality of each of his artwork, a collective history.

How does he make use of the aged hanji he has found to create his artworks? He uses them to wrap up countless individual polystyrene triangles and painstakingly ties a thin but strong string around each before gluing them onto two-dimensional surfaces. To add to his sense of personal and collective history, the strings chosen for this task are extracted from the old books themselves.

Even then we cannot escape the fact that the little triangular packages in his artworks hold only polystyrene: the meaning of the old text on the hanji bears not the slightest resemblance to what it envelops. This echo of hollowness is disguised by the busy buzz of profound speak arising from the Korean and Chinese characters imprinted on the mulberry paper. And out of this chaotic chorus of authors’ voices arises a new message.

This makes each triangular package “the basic unit of information” that becomes “the basic cells of life that only exist in art. By attaching these pieces one by one to a two-dimensional surface, (Chun wants) to express how the basic units of information can create harmony and conflict with each other”.

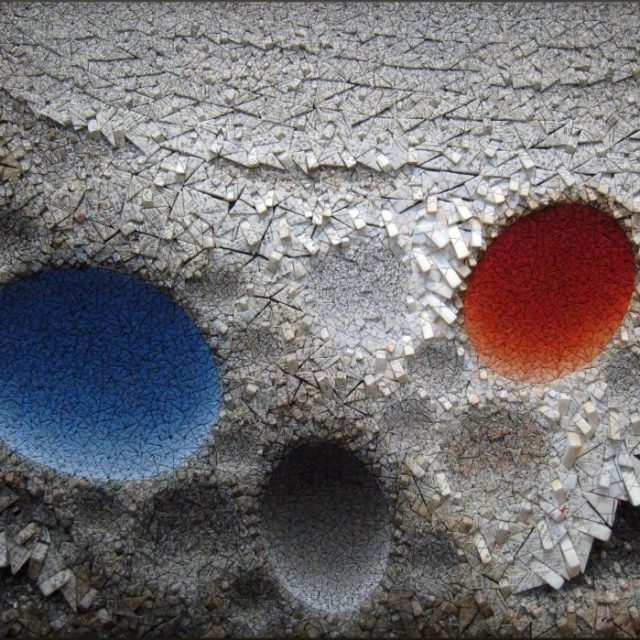

Thus his “Assemblage” artworks are rife with triangular packages at tightly held colliding juxtapositions to each other; resulting in assembled works heavily imbued with meaning greater than the sum of the parts. There is clearly evident an unending clash of divergently differing individual and societal ideas, leaving ever persistent life-breaking changes and haunting scars.

And what do his artworks say? Given the persistent inner turmoil that haunted Chun during his stay in America, it comes as no great surprise that his post-1995 body of artworks “reflects the (negative) history of human life… (with) all units and the natural, social groups they constitute… dynamically conflicting with each other… (Thus, chronologically documenting) the force and direction of their energy”.

Undoubtedly, some of his artworks reflect what happens when “two nations (are) at war constantly” – “their borders (change in ways that leave) scars on their neighbouring countries”. Others dwell on the time “ten(s) of millions of years ago (when) the earth’s tectonic plates collided, creating deep ocean trenches and high mountains”; and so bear sharp jutting “projections and (craters) all over the (lunar) surface”; metaphorically alleging to the tragic reality of the human condition and his exploitation of nature as well.

But it is not all doom and gloom: there exists in his lunarscape-like artworks’ stretches of smoother surfaces that speak of possible respite. On these planes, Chun plays with light in two ways.

Firstly, he makes use of subtle differences in blue and orange-red colours and shades – achieved by taking the Korean sensibility of living a sustainable life: he paints the hanji with natural vegetable dyes distilled in vats of boiling water before tying them round the polystyrene triangles.

Secondly, he strategically places the unstained hanji-wrapped triangles so that stretches of text-laden ones form an endless expanse of shadowy black. And as the wrapped triangles progress in less chaotic laid down bands of lesser to absent text, so Chun effectively and aesthetically creates a fluid gradation of darkness to light that is as sublimely clear as white.

And how has his childhood’s first memory of his beloved mother also been a significant influence on some of his artwork? Well, Chun’s latest series of artworks pay reverent homage to this special lady, deceased exactly a decade ago.

And though they are also assembled together with his mulberry paper wrapped polystyrene triangles, the tiny parcels are not laid in heavy juxtapositions against each other. Instead, the end result is very much a tranquil smooth finish, giving rise to planes of open surfaces very much like the endless sweeps of prairies undulating ever so gently in America.

His choice of colours reflect his fond memories of her as well – Chun uses soothing shades of restful lavender and powdery baby blue or gentle peach, tender beige and earthly brown. These personify the adoring child he once was (and still is) with his strong maternal bond to the woman who lovingly brought him into the world and devotedly nurtured him into the young man he once grew to be.

Fortunately for us, although Chun obviously creates art that make meaning of his world, he prefers the viewers of his artwork to read into his work at will. That lies in his strong belief that an artwork of 2 plus 2 does not automatically add up to 4 for an artist. It therefore offers the liberty of yielding 6 to some of us and 8, 10 or even 15 to others. He joyfully welcomes the interpretations each will bring to his works.

Do not miss the opportunity to give your own individual take on Chun’s unique masterpieces displayed at Art Plural Gallery, 38 Armenian Street, Singapore 179942. His “Assemblage” exhibition ends on 31 August this year.

Singart

Singart