Burnings Freeing Hanibal Srouji’s Soul

History appears to repeat itself in Lebanon: as in its Civil War from 1975 to 1990, thousands of Lebanese youths are again fleeing the country. This time with Germany or Sweden as their final destination; rather than to the west in general, Latin America and Africa 25 to 40 years earlier.

While the 1948 and 1967 influx of 100,000 Islamic Palestinian refugees running away from the newly formed Israel shifted Lebanon’s demographic balance from the significant influence of elites among its Maronite Christians to favour its Muslim population, and thus triggering its 25 year long Civil War, the current more than 1 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon is 1 catalyst to the unrest the nation faces today.

Arising from Syria’s own civil war triggered by the Syrian government’s violent crackdown on peaceful anti-government demonstrations in early 2011, as part of the Arab Spring, these once again freely settled displaced Syrians now represent 1 in 5 people in Lebanon, bringing the country near its previously projected population levels for 2050 – an issue the Lebanese government has failed to deal with amidst unaddressed endemic corruption, political dysfunction, and rising unemployment, inequality and poverty – all as its politicians’ means to “keep its people as servants begging at their doorsteps”[1].

How then does artist Hanibal Srouji feel about his decision to resettle back in Beirut since 2010? After having been one of the endless number of Lebanese who had fled Lebanon in 1976 to live first in Canada and subsequently in France, where he has made his name in the western world creating his signature art.

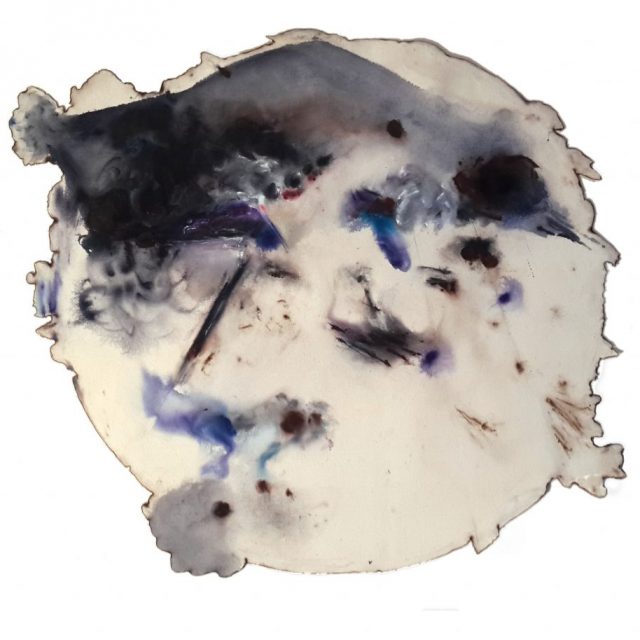

Those displayed in Intersections Gallery’s current “Burning Landscapes” exhibition offer hints to these very sentiments: on show are his since-the-1990s ongoing successions of “Healing Bands” and his more recent series “Tondo” – all created after he had taken up an Associate Professor position at the Beirut-based Lebanese American University; freeing him to concurrently live and work there and France.

They are artworks brought to life by his unchanging technique of burning his paintings with a blowtorch; leaving traces of charred boundaries and holes as markings on the canvases – a creative process evoking imageries of literal horror-movie magnitude of destruction of his country of birth he had personally experienced while serving as a Red Cross volunteer in Southern Lebanon during its Civil War; of Beirut’s endless bullet-marked walls of crippled buildings and of the total wreckage his own house had sustained that ultimately drove him, in his late teens, to sail from Sidon to Cyprus before emigrating to Montreal in Canada.

“Burning the canvas is a kind of drawing – it is about the consumption of the support itself; it is a motif of war,” Srouji explains.

And his “Tondo” series are burnt paintings on round canvases; referring to the portholes through which he, like countless other Lebanese, had gazed out onto the storm tossed oceans that swept them away from the Middle East they had called home; and signifying the opening of the spirit from which they could look beyond as they began their arduous journey of self renewal as promised by the compactly rolled up rectangular strips of talismans they had brought along – good luck charms that subsequently inspired Srouji to unceasingly recreate, and which eventually morphed into his world renowned yet equally charred “Healing Bands” – paintings on independent strips of canvas that hang and float free in the air; symbolizing his determination to free the canvas from its support, and thus infuse himself with an ode to cherished freedom.

Consequently his artistic burning process “has become a decorative motif, a musical motif” as Srouji further elaborates, “Now we can take this motif and play with it. The war is far behind. I was 18 when the conflict started. I lived through it and beyond it.”

In turn, his discreet touches and treatment of light and quietness resolutely hint at an artistic message of hope; painting landscapes, chips and fragments of dreams that illuminate the canvas – seeking to show how beauty, tranquility and fire can be adjoined together, intimately linked to the point of forming one buoyant expression. Srouji’s work becomes an allegory specific to the whole of Asia, where we can find the principle of the Ying and the Yang: the artistic unification on the same canvas of destruction and resilience of life – the inflicted devastation by fire has been transformed into a real aesthetic infused with optimism and creativity.

Unsurprisingly then though his earlier artworks speak of those landscapes he had been forced to leave, of those he had subsequently discovered and are in the process of being built, they also inevitably talk about Srouji as a nomad.

“I have been floating for 30 years… My roots are here in Lebanon,” he shares.

So he holds onto his childhood memories of Beirut in the 1960s and early 70s, when neon signs lit the centers of the city – a former major cultural-, commercial-, financial- and tourist-magnet after World World II, that had disintegrated with the outbreak of the Civil War; with his present works of light and colour on burnt canvases as signs of rebirth – of the hope for that light to shine once more, in spite of today’s difficult times.

For Srouji, Beirut may well from its ashes arise to its once glorious status as the Paris of the Middle East.

Gaze into Hanibal Srouji and Lebanon’s irrevocably entwined souls before “Burning Landscapes”, his joint exhibition with Singapore-based French-Lebanese fire-playing ceramist Tania Nasr at Intersections Gallery, 34 Kandahar Street, Singapore 198892, ends on 30 April.

Note:

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/06/lebanese-refugees-nobody-wants-stay-lebanon-miserable-life & http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14647308

Singart

Singart